Hugh Thompson

Hugh

Thompson was a US helicopter pilot that saved the lives of hundreds of

villagers in My Lai, Vietnam that were being attacked by other members

of the US military. The victims were unarmed, mostly women and children.

Despite his courageous intervention which began after the killings had

already commenced, about 400 were killed in this village alone.

See the tribute to his life below, written when he passed away in 2006

Hugh

Thompson was a US helicopter pilot that saved the lives of hundreds of

villagers in My Lai, Vietnam that were being attacked by other members

of the US military. The victims were unarmed, mostly women and children.

Despite his courageous intervention which began after the killings had

already commenced, about 400 were killed in this village alone.

See the tribute to his life below, written when he passed away in 2006

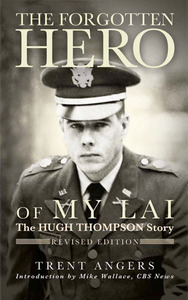

You can read his story in the book The Forgotten Hero of My Lai, The Hugh Thompson Story. Get the book directly from the publisher or your local bookstore. The revised edition shows President Nixon and some of his political allies in the House of Representatives interfered in the judicial process to try to prevent any U.S. soldier from being convicted of war crimes.

Another book of interest on the subject of US military intervention in Vietnam is "Kill Anything that Moves. The Real American War in Vietnam" by journalist Nick Turse. Turse gives ample evidence that the My Lai massacre was actually quite routine in the US effort to destroy "the enemy".

Hugh Thompson and My Lai

There is an Ugly American, a Quiet American and then there’s Hugh

Thompson, the Army helicopter pilot who, with his two younger crew

mates, was on a mission to draw enemy fire over the Vietnamese

village of My Lai in March, 1968. Hovering over a paddy field, they

watched a platoon of American soldiers led by Lt. William Calley,

deliberately shoot unarmed Vietnamese civilians, mainly women and

children, cowering in muddy ditches. Thompson landed his craft and

appealed to the soldiers, and to Calley, to stop the killings.

Calley told Thompson to mind his own business.

Thompson took off but then one of his crew shouted that the shooting

had begun again. According to his later testimony, Thompson was

uncertain what to do. Americans murdering innocent bystanders was

hard for him to process. But when he saw Vietnamese survivors chased

by soldiers, he landed his chopper between the villagers and

troopers, and ordered his crew to fire at any American soldiers

shooting at civilians. Then he got on the radio and begged U.S.

gunships above him to rescue those villagers he could not cram into

his own craft.

On returning to base, Thompson, almost incoherent with rage,

immediately reported the massacre to superiors, who did nothing,

until months later when the My Lai story leaked to the public. The

eyewitness testimony of Thompson and his surviving crew member

helped convict Calley at a court-martial. But when he returned to

his Stateside home in Stone Mountain, Georgia, Thompson received

death threats and insults, while Calley was pardoned by President

Nixon. Indeed, for a time, Thompson himself feared court-martial.

Reluctantly, the massacre was investigated by then-major Colin

Powell, of the Americal Division, who reported relations between

U.S. soldiers and Vietnamese civilians as "excellent"; Powell’s

whitewash was the foundation of his meteoric rise through the ranks.

Hugh Thompson died last week, age sixty two. Thirty years after My

Lai, he, and his gunner Lawrence Colburn, had received the Soldiers

Medal, as did the third crew member, Glenn Andreotta, who was killed

in combat. "Don’t do the right thing looking for a reward, because

it might not come," Thompson wryly observed at the ceremony.

Something stuck in my head when I learned of Thompson’s death.

"There was no thinking about it," he said before his death. "There

was something that had to be done, and it had to be done fast."

Words similar to these are often used by combat heroes to describe

incredible feats of courage under fire. With one possible

difference. According to the record, Thompson did have time to think

about it as he took off from My Lai, hovered and tried to wrap his

mind around the horror below. Then he made a conscious decision to

save lives. Some of the Vietnamese he rescued, children then, are

alive today.

Ex-chief warrant officer Thompson is a member of a small, elite

corps of Americans who have broken ranks and refused to run with the

herd. They include Army specialist Joseph Darby, of the 372d

Military Police Company, who reported on his fellow soldiers who

were torturing prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison. His family has

received threats to their personal safety in their Maryland

hometown. And Captain Ian Fishback, the 82d Airborne West Pointer,

who served combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, and tried vainly

for seventeen months to persuade superiors that detainee torture was

a systematic, and not a ‘few bad apples’, problem inside the U.S.

military. In frustration, he wrote to Senator McCain, which led

directly to McCain’s anti-torture amendment. I wouldn’t want to bet

on the longevity of Captain Fishback’s military career.

Thompson’s death also reminded me of Captain Lawrence Rockwood [see

here], of

the 10th Mountain Division. Ten years ago, Rockwood was deployed to

Haiti where, against orders, he personally investigated detainee

abuse at the National Penitentiary in the heart of Port au Prince.

He was court-martialed for criticizing the U.S. military’s refusal

to intervene, and kicked out of the Army. While still on duty, he

kept a photograph on his desk of a man he greatly admired. It was of

Captain Hugh Thompson.

Some of my friends get so angry at the Bush White House, and so despairing, that they slip into a mindset where Americans – the great ‘Them’ out there – are lumped into a solid bloc of malign ignoramuses. They forget that this country is also made up of people like Hugh Thompson, Joe Darby, Ian Fishback and Lawrence Rockwood – outside and inside the military.